Herd Your Clusters Like Cattle: How We Automated our Clusters

This is a cross-post from the original post on LinkedIn.

In 2020, it took one engineer about a week to create a new Kubernetes cluster integrated into the Cruise environment. Today we abstract all configurations and creating a new cluster is a matter of one API call, occupying essentially no engineering hours. Here is how we did it.

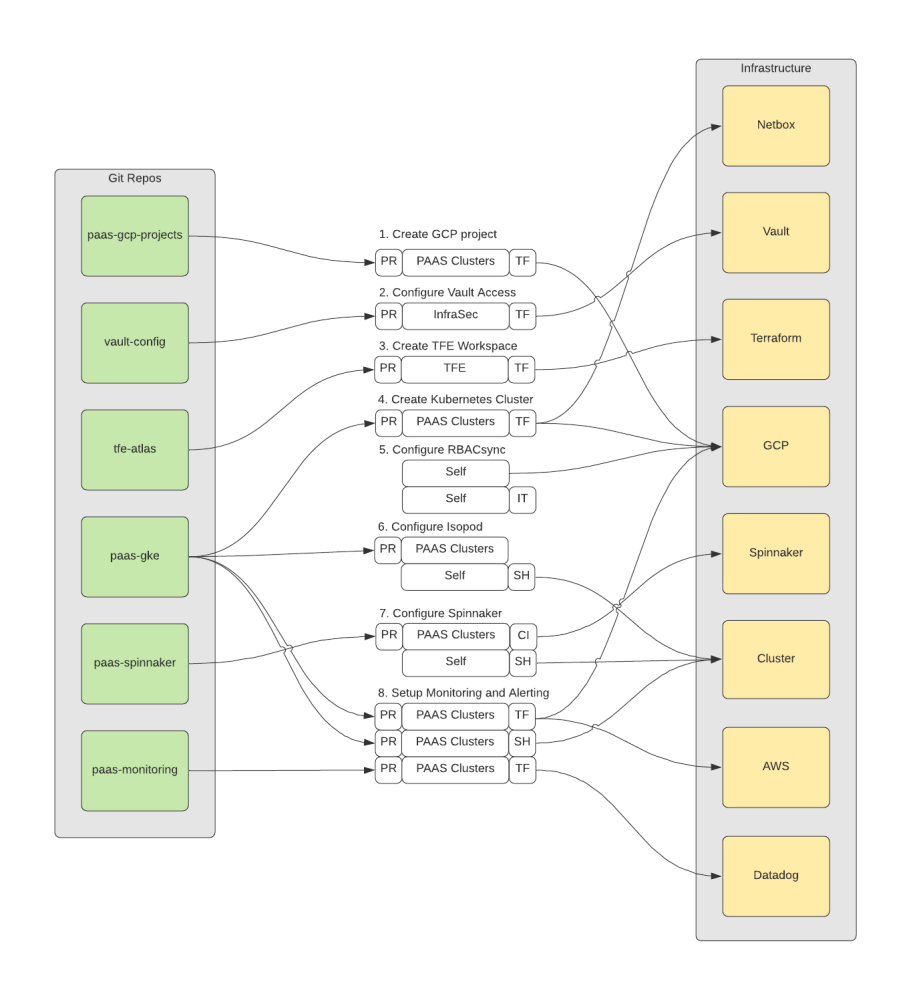

Before, every platform engineer knew each individual Kubernetes cluster by name and whether the workloads running on it were business critical or not. There was an entire set of always running test clusters to rollout new features. Creating a new cluster meant for an engineer to follow a wiki guide that walks you through the exact sequence of steps that has to be performed to create a cluster. That involved a bunch of pull requests to many different repositories. These pull requests had to be executed in a certain order and success of a previous step unblocked another step (like creating a new Terraform Enterprise workspace before applying Terraform resources). The following is already a simplified flow chart of what an engineer had to perform.

While Cruise is using managed Kubernetes clusters on the cloud which technically can already be created with only one API call, there is a bunch of customization that Cruise does to every new cluster. That includes but is not limited to:

- Claiming free CIDR ranges for masters, nodes, pods and services and register them on netbox

- Integration into the internal VPC

- Firewall configuration

- Authorized network configuration

- Creation of cluster node service account and IAM bindings

- Customizing the default node pool

- Creation of a dedicated ingress node pool

- Configuring private container registry access for nodes

- Creating load balancer IP address resources

- Creating DNS record entries

- Creating backup storage bucket

- Vault integration (using the Vault Kubernetes Auth Method + configuring custom Vault roles)

- Configure API monitoring

- Install cluster addons (istio, coredns, external dns, datadog agent, fluentd, runscope agent, velero backup and custom operators to only name a few)

Decommissioning clusters was a simpler but still pretty involved process. Extensive creation and decommissioning processes lead us to treat our clusters as pets.

You might ask “But Why is That Bad? - I Love Pets!”. While pets are pretty great, it’s not favorable to treat your clusters like pets, just as it is not favorable to treat virtual machines like pets. Here are a few reasons why:

- It takes time (a lot) to create, manage and delete them

- It is not scalable

- We often conduct risky ‘open heart surgeries’ to save them

- We can’t replace them without notice to users

- We are incentivized to have fewer clusters which increases the blast radius of outages

However, here is what we would like to have:

- Clusters don’t have to be known individually, they’re all just an entry in a database identified by unique identifiers

- They’re exactly identical to one another

- If one gets sick (dysfunctional) we just replace it

- We scale them up and down as we require

- We spin one up for a quick test and delete it right after

All these attributes would not apply to pets, but it does sound a lot like cattle. Bill Baker first coined this term for IT infrastructure in his presentation “Scaling SQL Server” in 2012 [1], [2], [3]. He implied that IT infrastructure should be managed by software and an individual component (like a server) is easily replaceable by another equivalent one created by the same software.

That’s what we have achieved at Cruise through the cluster-operator, a Kubernetes operator that reconciles custom Cluster resources and achieves a desired state in the real world via API calls through eventual consistency.

Bryan Liles’ (VP, Principal Engineer at VMWare) tweet on 1/4/2021 of which Tim Hockin (Principal Software Engineer at Google & Founder of Kubernetes) was affirmative:

I often think about Kubernetes and how it rubs people the wrong way. There are lots of opinions about k8s as a container orchestrator, but the real win (and why I think it is great) is the core concept: Platform for managing declarative APIs. Infra APIs have never been better.

— Bryan Liles (@bryanl) January 4, 2021

Even though work for the cluster-operator started before that tweet, it is yet a perfect expression for what we were trying to achieve: A declarative infra API that expresses a desired state and a controller that asynchronously reconciles to eventually reach that desired state. We utilized kubebuilder for the original scaffolding of our operator. Kubebuilder is maintained by the kubernetes special interest group and creates an initial code base with all best practices for controllers (using controller-runtime under the hood). That includes watchers, informers, queuing, backoff retry, and the entire API architecture including automatic code generation for the custom resource definitions (CRDs). All we had to do was to create controllers and sub-controllers and fill the reconciliation stubs with business logic. Kubebuilder is also used by other major infrastructure operators like the GCP Config Connector and the Azure Service Operator.

Based on the API we defined as go structs, a custom Cluster resource could look like the following:

apiVersion: cluster.paas.getcruise.com/v1alpha

kind: Cluster

metadata:

name: my-cluster

namespace: clusters

spec:

project: cruise-paas-platform

region: us-central1

environment: dev

istio:

enabled: true

ingressEnabled: true

template:

spec:

clusterAutoscaling:

enabled: false

minMasterVersion: 1.20.11-gke.13001

The creation of this Cluster resource triggers the main control loop to create sub-resources needed by every cluster. Some of them are proprietary and are reconciled again by other inhouse controllers (examples are a netbox controller that automatically carves out new CIDR ranges for new clusters, a vault controller that automatically sets up the kubernetes auth for the new cluster or a deployment controller that triggers Buildkite deployments via API, among others). Some others are cloud provider specific resources like the ContainerCluster (which is the actual cluster itself), ComputeSubnetwork, ComputeAddress, ComputeFirewall, IAMServiceAccount and others. Those cloud provider specific resources would get reconciled by the GCP Config Connector in this case, so we didn’t have to implement the GCP API layer and authentication. All we had to do was to communicate with the Kubernetes API server and create those resources. At the time of writing the creation of the Cluster resource triggers the creation of 16 such sub-resources. The relationship between the root controller for the Cluster resource and all sub-resources, which themselves could have sub-resources again, resembles a tree data structure consisting of controllers and their resources.

The yaml of the Cluster resource above can easily be created on a cluster running the operator via kubectl apply -f cluster.yaml and deleted the same way. All provisioning and decommissioning is then handled by the tree of controllers. We created a helm chart around this in which a list of clusters is maintained. The helm chart then applies all the Cluster resources. That way cluster creation and decommissioning is still tracked and reviewed via git ops and it’s bundled in a single PR of a few lines with essential properties. In fact most of the properties are defaulted as well, so that you could hypothetically create a Cluster resource just with a name set.

Of course this is also available via the raw Kubernetes API under /apis/cluster.paas.getcruise.com/v1alpha1/clusters which makes this integratable with any other software. Imagine a load test that spins up a cluster, performs the load test, stores the result and deletes the cluster right after.

Notice the difference between .spec and .spec.template.spec in the Cluster resource above. While .spec is supposed to hold generic, cloud agnostic properties defined by us, the .spec.template.spec holds cloud vendor specific properties, much like the equivalent template spec on a Kubernetes native deployment that contains the spec of the underlying desired pod. This is realized through a json.RawMessage struct field that allows for any arbitrary json/yaml on that field. It gets parsed into a map[string]interface{} for further usage and its properties are used to override the chosen defaults on the core ContainerCluster resource. It is important to preserve unknown fields via // +kubebuilder:pruning:PreserveUnknownFields to allow the input yaml/json to contain any fields the cloud provider specifies (or will specify in the future).

Conclusion

This cluster provisioning and decommissioning via a single API call has allowed us to treat clusters as cattle. We create them for quick tests and experiments, delete them again, move noisy neighbors to dedicated clusters and manage the properties and configuration of all our clusters centrally. Clusters are owned by well tested production-grade software and not by humans anymore. What used to cost days of engineering work was minimized to a few minutes of human attention to enter some cluster metadata. We’re not only automating a fleet of cars, but also a fleet of clusters.

Tags: kubernetes, cncf, clusters, infrastructure, automation, api, controllers, operators